Standards for responsible business conduct

Standards help clarify human rights expectations for businesses. They can serve as a basis for harmonization within and across industries. However, many standards lack operational guidance, and their voluntary nature creates risks for inconsistent implementation and greenwashing.

Foundational normative standards

Three key international frameworks set out baseline expectations for how companies should respect human rights: the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights, the OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises, and the ILO Core Labour Conventions. For a more in-depth discussion, see section 1.

While the UNGPs explain what companies are expected to do, they provide limited detail on how to do it. The OECD Due Diligence Guidance for Responsible Business Conduct, especially its sector-specific versions, provides more operational detail. Still, many companies—particularly smaller ones—find it complex to understand, let alone apply. To bridge this gap, a growing body of practical guidance has emerged that can help businesses implement due diligence (see Section 6).

Voluntary Sustainability Standards (VSS)

Voluntary Sustainability Standards translate broad expectations into specific principles and criteria that companies can follow. Over time, many of these standards have integrated explicit human rights (due diligence) requirements. While not legally binding, VSS are widely used by companies to showcase their own commitments to human rights, and to communicate expectations to business partners.

Useful resources:

- The Amfori Business Social Compliance Initiative (BSCI) Code of Conduct covers labour rights in global supply chains based on ILO conventions. It contains explicit due diligence obligations based on the OECD Guidance.

- The ISO 26000 standard offers non-certifiable guidance on how to integrate social responsibility (including human rights) into organizational processes.

- The Fair Labour Association (FLA) Workplace Code of Conduct is based on ILO standards and is used primarily in B2B relations in the apparel and agricultural sector.

- The Ethical Trading Initiative (ETI) Base Code is based on the ILO conventions and serves as a reference framework for many companies' supplier codes of conduct. It is closely associated with the SMETA auditing methodology (see below)

Useful resources:

- The Responsible Business Alliance (RBA) Code of Conduct is widely used in the electronics and ICT sector, and covers environmental compliance, labour rights, health and safety, ethics, and due diligence requirements, particularly in relation to mineral sourcing.

- The Fair Wear Foundation Code of Labour Practices is primarily used in garment factories

- Fairtrade Standards cover a wide range of agricultural products (e.g. coffee, cocoa, cotton) and have a strong focus on smallholder rights and fair trading practices.

Tools for risk identification and monitoring

Standards set out what is expected from companies—but businesses also need tools to identify where risks exist, and to verify if the expectations they are setting internally and towards business partners are being met in practice.

Social audits

Social audits remain the most common method for assessing human rights compliance in global value chains. They usually involve on-site inspections of workplaces, focusing on issues like working conditions, health and safety, and working hours. Audits are often used to check compliance with supplier codes of conduct or with VSS. However, as discussed in Section XX, audits face growing criticism. They can miss serious and systemic problems—such as discrimination, harassment, or freedom of association violations—that are harder to detect through short, checklist-based inspections.

Commonly used auditing schemes

- SMETA (Sedex Members Ethical Trade Audit): A widely used auditing methodology. It tells auditors how to conduct audits and to report the findings. While SMETA does not tell auditors what to audit (i.e. in the form of a standard), in practice it is designed to audit against the ETI Base code and local law.

- The RBA Validated Assessment Program (VAP) is a widely used audit protocol in the Electronics and ICT sectors, that is aimed at verifying compliance with the RBA Code of Conduct. It includes a scoring system, and is often used for supplier screening and monitoring.

- FLOCERT (Fairtrade Certification Audits) is the official certifying body for Fairtrade Standards. It audits producers, plantations, and traders based on a range of criteria including child labour, forced labour, working conditions, and democratic governance. It is widely used in agricultural supply chains such as coffee, cocoa, and cotton.

Worker-driven monitoring

In response to the shortcomings of conventional audits, a number of initiatives have developed under the banner of worker-driven monitoring or worker-driven social responsibility (WSR). These initiatives put workers—or their legitimate representatives—at the center of the monitoring process. While still relatively few in number, they provide valuable lessons for the future of due diligence: effective verification cannot rely solely on standardized, top-down procedures, but must also empower rights-holders and ensure independent oversight.

Worker-driven monitoring

- The Fair Food Program (FFP) originated in the US agricultural sector, and is based on legally binding agreements between farmworker organisations and major food retailers. It includes regular, unannounced audits, worker-to-worker education, and a 24/7 complaint hotline. Participating buyers commit to suspend purchases from suppliers that fail to remedy violations.

- Electronics Watch is a European monitoring organisation that supports public sector buyers in implementing and promoting due diligence in electronics supply chains. It operates through binding contract clauses between public buyers and suppliers, and commissions independent monitoring based on worker- and civil society participation. Initially focused on electronics manufacturing, Electronics Watch is expanding its monitoring efforts into the extractives industries.

Benchmarks

Benchmarks assess and compare companies' human rights performance based on publicly available information. They typically operate at the company level, creating reputational incentives for businesses to improve. They are also used by investors, civil society, regulators, and public buyers to identify leaders and laggards.

Human rights benchmarks

- The World Benchmarking Alliance develops and maintains several benchmarks that relate to BHR issues. In addition to an overarching "Social Benchmark" and more specific benchmarks on issues like gender and digital rights, the Corporate Human Rights Benchmark (CHRB) assesses companies based on their governance, due diligence processes, remedy systems, and overall alignment with the UNGPs.

- KnowTheChain focuses specifically on forced labour risks in global supply chains, and covers companies in the apparel, electronics, and food & beverage sectors. It evaluates company performance in areas like recruitment practices, worker voice, and traceability.

Digital solutions

An ever-widening range of digital solutions promise fast, data-driven insights into human rights risks. These tools use technologies like mobile worker surveys, geospatial analysis, AI-driven risk scoring, and data mining. In some cases, they can complement traditional audits. In others, they claim to remove the need for auditing.

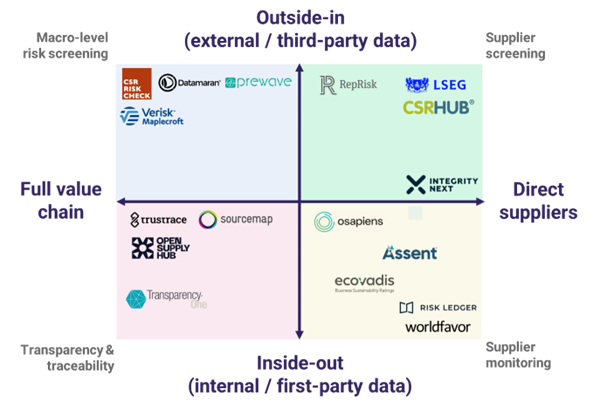

Two factors help distinguish between different types of digital solutions:

- Value chain scope: ranging from full value chain to direct business partners.

- Type of data: ranging from exclusive reliance on external, third-party data (outside-in) to an exclusive reliance on information collected directly from companies and workers (inside-out).

Based on these factors, we can identify four main types (see figure XX):

- Type I: Macro-level risk screening (outside-in, full value chain). Can help companies identify and prioritise high-risk products or geographies by analysing global datasets, indices, and media sources; but do not provide supplier-specific insights.

- Type II: Supplier screening (outside-in, direct business partners). Provides ratings or alerts on specific business partners. Often used to avoid reputational or legal risks.

- Type III: Transparency and traceability solutions (inside-out, full value chain). Focus on mapping supply chains across multiple tiers, sometimes using technologies like satellite data or blockchain.

- Type IV: Supplier monitoring (inside-out, direct business partners). Often integrated into procurement systems, and typically rely on self-assessments by suppliers. Sometimes paired with corrective action tracking or grievance reporting.

Figure 1: Non-exhaustive overview of digital solutions. This overview does not imply endorsement of any specific tool. Logos are used for identification purposes only

While digital solutions can certainly help companies to identify and track risks, and to organize data management at scale, they cannot replace the contextual understanding that comes from human judgement, nor replace the engagement and information rights of rights-holders and their representative structures. Without human interpretation, data can mislead—particularly because datasets are partial, uneven in quality, and prone to bias. Moreover, every solution has shortcomings, so effective use would still require cross-checking multiple data sources, validating with those affected, and ensuring findings are interpreted in light of local realities.

Industry and multi-stakeholder initiatives

Industry initiatives and multi-stakeholder initiatives are collaborative platforms where companies, civil society, and sometimes governments work together to address human rights risks. While participation is largely voluntary, many of these initiatives influence entire sectors through the development of shared frameworks, and by building leverage and capacity to implement them.

Key differences between initiatives include:

- Scope: Some focus narrowly on specific human rights risks (e.g. child labour, health and safety), while others address a broader set of rights. Initiatives may be sector-specific or cross-sectoral.

- Governance: Industry initiatives are typically led and funded by companies. Multi-stakeholder initiatives have more balanced governance, involving NGOs, trade unions, and sometimes governments.

- Standards: Some initiatives are built around formal standards or codes of conduct, while others focus more on guidance and joint action without requiring adherence to a formal standard.

- Activities: Can range from training and capacity building, to problem-solving, advocacy, benchmarking, or maintaining grievance mechanisms.

- Verification: Some rely on self-assessments, while others use independent third-party verification.

- Stakeholder engagement: most initiatives rely on some form of external stakeholder engagement. Yet the depth of this engagement may vary from active involvement in decision-making to limited advisory roles.

| Initiative | Sector | Governance | Standards | Activities | Verification | Stakeholder engagement |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amfori BSCI | Multi-sector | Industry-led | BSCI Code of Conduct (based on ILO, UNGPs, OECD) | Supply chain monitoring, training, member support tools | Third-party social audits | Industry-led with stakeholder advisory channels and local engagement networks |

| Ethical Trading Initiative | Multi-sector | Multi-stakeholder (industry, NGO's, trade unions) | ETI Base Code (based primarily on ILO) | Capacity building, advocacy, member accountability framework | Independent assessments of member performance and reporting | Equal governance role for trade unions and NGO's, worker voice integrated into monitoring |

| Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO) | Agriculture (palm oil) | Multi-stakeholder (industry, NGOs, smallholders, finance) | RSPO Principles & Criteria (aligned with, ILO, UNGPs, OECD) | Community engagement, grievance redress system, market incentives | Third-party certification audits by accredited bodies | NGOs, smallholders, and community representatives involved in governance, accessible grievance mechanism |

| Sustainable Agriculture Initiative (SAI) Platform | Agriculture | Industry-led (food & beverage companies) | No standard. Benchmarking framework Farm Sustainability Assessment aligned with ILO, UNGPs, OECD. | Farmer capacity building, self-assessment tools, industry benchmarking | Self-assessments with optional third-party verification | Engagement with some producer groups, but governance dominated by companies |

| Initiative for Responsible Mining Assurance (IRMA) | Extractives | Multi-stakeholder (industry, NGOs, trade unions, communities) | IRMA Standard for Responsible Mining (based on ILO, OECD, UNGPs) | Stakeholder engagement, grievance channels | Independent third-party audits with public scoring | Communities, workers and NGOs involved in governance, robust grievance and consultation mechanisms |

| International Council on Mining and Metals (ICMM) | Extractives | Industry-led (member companies only) | ICMM Mining Principles (aligned with UNGPs, OECD, ILO) | Implementation guidance, peer learning, public reporting framework | Self-assessments, third-party assurance of sustainability reports | Engagement via consultation only |

| Fair Wear Foundation (FWF) | Garments & textiles | Multi-stakeholder (industry, NGOs, unions) | Code of Labour Practices (ILO, OECD, UNGPs) | Complaints mechanism, brand performance checks | Factory audits, worker complaints mechanism | Trade unions involved in governance, strong worker involvement in grievance and remediation |

| Sustainable Apparel Coalition (SAC) | Garments & textiles | Industry-led | No standard, but Higg Index: assessment tools covering social impacts (aligned with ILO, UNGPs, OECD) | Data sharing platform, member training, benchmarking | Self-assessments with optional third-party verification | Stakeholder inputs via consultations, no formal governance role |

| Building Responsibly | Construction, engineering, infrastructure | Industry-led coalition with NGO engagement | Worker Welfare Principles Framework (ILO, UNGPs) | Peer learning, implementation guidance | Self-assessment; no independent audits | NGO advisory input, no formal worker/community governance role |

Table 1: Comparison of influential industry- and multi-stakeholder initiatives in high-risk sectors (non-exhaustive, based on publicly available information from these initiatives, and secondary research and evaluations (MSI integrity, OECD reports, ISEAL alliance, mapping))

Belgian support for MSIs

In recent years, Belgian national and regional governments have explicitly supported two initiatives to foster responsible business conduct in high-risk sectors. TruStone was initiated by the Flemish government together with the Netherlands, brings together natural stone companies, sector federations, trade unions, NGOs, and public authorities (in their capacity as public buyers). Trustone aims to tackle human rights abuses and environmental risks in global stone supply chains, particularly in India and China. It combines shared risk assessments, company action plans, and independent monitoring, while also creating leverage through public procurement commitments.

In the food sector, Beyond Chocolate is a Belgian partnership agreement involving companies, civil society, certification bodies, and government. Its central ambition is to ensure that all chocolate produced and sold in Belgium is sustainable by 2025, and that cocoa farmers receive a living income by 2030. The initiative builds on international but adapts them to Belgian market realities, using joint monitoring and reporting to hold participants accountable.

Social dialogue

Social dialogue is an established, formal and institutionalized process that is rooted in the relationship between employers and employees. It refers to discussions, negotiations, and information exchanges between employers and workers (often represented through trade unions). It can take place at different levels —workplace, sectoral, national, or international— and is recognized by the ILO as a key means of promoting decent work.

Social dialogue and due diligence can act as mutually reinforcing processes essential for responsible business conduct. Both due diligence and social dialogue are process-oriented, preventive, and based on continuous consultation. Effective due diligence requires meaningful consultation with affected groups across the value chain, with a key role for workers' organizations, as emphasized in the ILO MNE Declaration (Paragraph 10 (e)). Social dialogue can enable companies to gather crucial insights on human rights risks and solutions, making due diligence more robust and participatory. In turn, due diligence has the potential to strengthen social dialogue by encouraging companies to assess whether rights like freedom of association and collective bargaining are upheld, and by supporting ongoing stakeholder engagement.

Bipartite social dialogue and HRDD

Several European trade unions are establishing links between existing social dialogue structures and future due diligence obligations at company level. The Dutch trade union CNV International developed a measurement tool, the Fair Work Monitor, to obtain insights in the working conditions in global value chains. They then try to establish a dialogue with the suppliers on the findings of these studies, also engaging the international buyers in this sector. In a number of cases this has resulted in action plans that are developed with the companies to improve the situation on the ground, covering themes such as occupational safety and health, social dialogue and collective bargaining. German trade unions are using the German Supply Chain Act to promote social dialogue in low-income countries.

Useful resources:

In the context of the TruStone initiative (see section xxx), Belgian and Dutch trade unions are supporting importers of natural stone to encourage their suppliers in low-income countries to engage with local civil society organisations and trade unions, with the aim of gradually establishing dialogue. Belgian trade unions are also exploring the role of national and European works councils in HRDD sustainability reporting. The works councils are a central body for social dialogue at company level for companies with more than 50 employees. In line with the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD), employers and trade unions can engage on the quality and content of sustainability reporting during the works council as part of the Economic & financial information (EFI).

Global Framework Agreements (GFA)

A Global Framework Agreement is a specific form of cross-border social dialogue. It is negotiated directly between a multinational company and one or more global union federations. It commits the company to respecting core labour rights (cf the ILO standards) across all of its operations and, in many cases, across its supply chain.

Unlike MSIs, GFAs create a direct and formal relationship between the company management and workers' representatives. They draw on trade unions' legal mandate to represent workers, are often linked to grievance and dispute-resolution mechanisms, and typically include joint monitoring mechanisms such as workplace visits or review committees.

While GFAs can strengthen labour rights protection, their effectiveness depends on trade union capacity, company commitments, and local enforcement capacity. Coverage is often limited to a subset of the workforce, and implementation may be weaker in contexts with restrictive labour laws or limited worker organization.