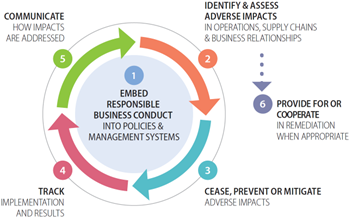

Identifying and prioritizing risks

Taking action

Tracking and monitoring

Remediation

Communicating due diligence

Integration into management systems

The UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights (UNGPs) and OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises place due diligence at the heart of responsible business conduct. They clarify why due diligence matters, but offer limited hands-on guidance on how it should be implemented. To help fill that gap, the OECD created its Due Diligence Guidance for Responsible Business Conduct.

Identifying and prioritizing risks

Taking action to address risks

Once priorities have been set, companies must take action to address them. What actions are appropriate depends on how companies are connected with (potential) negative impacts. According to the OECD and the UNGPs, companies that directly cause or contribute to (potential) adverse impacts must take immediate action to stop, prevent, or–when necessary–remediate the harm. For instance, when companies fail to provide adequate health and safety equipment to workers working with hazardous chemicals, they should (temporarily) halt the activities causing acute health and safety impacts until the situation is rectified.

When companies are connected with (potential) adverse impacts through business partners–for instance, a supplier working with subcontractors who employ undocumented migrants working at very low wages–they should attempt to exercise leverage over these business partners in order to ensure that they take appropriate action to prevent harm. Companies can exercise leverage in different ways. Here, we focus on four key pathways:

- Contractual leverage: Human rights clauses can be inserted in contracts and supplier codes. Clauses are most effective when supported by credible monitoring and remediation, and when they reflect a shared responsibility between buyers and suppliers.

- Purchasing power: Procurement can be used to promote human rights. While some companies could opt to disengage with high-risk suppliers, disengagement rarely improves conditions on the ground, and should be the last resort. Instead, supplier engagement and positive incentives—such as better payment terms or preferred supplier status may be more effective.

- Capacity-building: Companies can support suppliers by offering targeted support, such as occupational health and safety training, or training on human rights awareness. This helps build local capacity to prevent and address risks.

- Collective action: Instead of working alone, companies can expand leverage by working together with others, through industry initiatives, multi-stakeholder platforms, or partnerships with trade unions and NGOs (more on this in Section XX).

Standard practice has long been to rely on pathway 1—top-down contractual requirements that may or may not be enforced through audits—sometimes combined with pathway 2—integration of human rights into procurement and supplier management. In some sectors (e.g. the gold industry), due diligence has led to risk avoidance, with companies steering clear of "high-risk" actors like artisanal miners.

In recent years, there is growing recognition that top-down due diligence approaches, which shift the compliance burden unilaterally to suppliers, are ineffective in mitigating human rights risks, and more constructive approaches are gaining ground. These approaches do not exclude pathways 1 and 2, but shift the balance towards pathways 3 and 4, by emphasizing burden-sharing, responsible contracting, stakeholder engagement, and capacity-building. Moreover, there is growing recognition that when disengagement becomes inevitable, it should be based on clear criteria, after genuine efforts to reduce harm, and with attention to potential consequences for affected stakeholders.

Tracking and monitoring

The OECD Guidance and UNGPs underline the importance of tracking the effectiveness of corporate actions to address human rights risks. Social audits remain the most common tool for monitoring human rights compliance in value chains. Audits can help companies obtain a better understanding of more visible human rights issues, such as compliance with health and safety standards. Yet, they face growing criticism for being superficial, infrequent, and vulnerable to conflicts of interest. In many instances, social audits fail to include meaningful inputs from (potentially) affected stakeholders. Moreover, audits can also be costly and burdensome, particularly for SMEs.

In response, interest in alternative monitoring mechanisms is growing. On the one hand, there are monitoring initiatives that place affected stakeholders (notably workers) at the centre of monitoring efforts. On the other hand, there is growing interest in the use of digital monitoring tools. We will explore the role and limitations of these tools in more depth in Section XXX.

Remediation

Even when companies carry out due diligence in good faith, they may still become linked with adverse human rights impacts. In such cases, they are expected to contribute to the remediation of harm. Again, appropriate remediation depends on the type and degree of involvement. When a company directly causes- or contributes to negative impacts, it is expected to directly provide-, or contribute to providing, access to remedy. When a company is linked with an impact through a third party, it should attempt to exercise leverage to encourage and support remediation by this third party.

Remediation can take different forms (not exhaustive):

- Financial compensation (e.g. for unpaid wages or medical costs);

- Rehabilitation and restoration (e.g. restoring access to water or land for communities);

- Public apologies and acknowledgment of harm;

- Changes to policies or practices (e.g. ending exploitative purchasing practices).

Whatever the form, remediation should always be informed by engagement with affected stakeholders. This means involving workers, communities, or consumers in identifying appropriate outcomes, instead of merely imposing solutions.

Communicating due diligence

Communication is key to building trust and promoting dialogue. While communication is increasingly equated with formal reporting (which will be discussed in depth in section XX), companies should not lose sight of broader, continuous communication efforts.

What and how a company should communicate depends on its context and audience. While communication efforts may be more or less elaborate, key elements include:

- A public commitment to human rights;

- An explanation of (potential) impacts the company may be linked with, and how these are identified;

- An overview of how the company is attempting to address these risks.

Companies can use different communication channels. As a general rule communication should be accessible to those potentially affected by the company's operations.

- A dedicated section in a formal sustainability report, which may or may not be aligned with sustainability reporting standards (see section XX)

- A dedicated section on the company website;

- Targeted stakeholder communications, such as tailored updates for employees or business partners;

- Investor briefings;

- Customer-oriented communication, such as social media posts.

Integrating due diligence into management systems

The OECD emphasizes that responsible business conduct must be embedded into how companies operate. This means integrating due diligence into policies, structures, and management systems. Integration typically involves several components:

- Developing clear policy commitments to human rights that are approved at the highest level, that reference key international standards, and that are publicly communicated.

- Assigning responsibility. A person or team should be designated to oversee the implementation of due diligence. Ideally, due diligence does not fall under the responsibility of a single department, but involves collaboration across different departments, including sustainability, legal/compliance, risk management, procurement, HR, and operations. In smaller firms, it may be handled by a single person wearing multiple hats. In both cases, responsible staff should have adequate resources and support to assume this responsibility.

- Involving leadership. Leadership plays a key role in setting the tone and in ensuring that respect for human rights becomes part of the business culture. Leaders must understand the company's main human rights risks, and should demonstrate their commitment to addressing these risks e.g. in public statements or by creating the right internal incentives.

- Embedding due diligence into everyday operations. This requires integrating risk identification and -mitigation into key business processes, such as procurement, mergers, or product design. It also means regular information-sharing across departments.

- Integrating due diligence into management systems. Notably, due diligence should become aligned with enterprise risk management systems, and reporting processes—where these are present.